Cucurbitacina

Las cucurbitacinas son unos compuestos químicos producidos en al menos algunos tejidos de todos los miembros de la familia Cucurbitaceae (y en algunas especies de otras familias de plantas); en la mayoría de las especies están concentradas en las raíces y los frutos, y en menor medida en tallos y hojas. Debido a su amargor extremo, se cree que están involucradas en la defensa de las plantas ante la herbivoría; siendo la excepción unas cuantas especies de escarabajos crisomélidos Aulacophorina y Diabroticina que las secuestran en su propio organismo y en su prole para propia defensa.[cita 1]

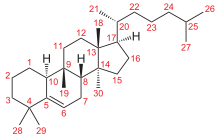

Las cucurbitacinas se clasifican químicamente como esteroides, derivados del cucurbitano, un hidrocarburo triterpénico. A menudo se encuentra naturalmente en forma de glucósidos.[15] Estos compuestos, y compuestos derivados se han encontrado en muchas familias de plantas (incluyendo Brassicaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Begoniaceae, Elaeocarpaceae, Datiscaceae, Desfontainiaceae, Polemoniaceae, Primulaceae, Rubiaceae, Sterculiaceae, Rosaceae, y Thymelaeaceae), en algunos hongos (incluyendo Russula y Hebeloma) e incluso en algunos moluscos marinos.

En medicina y veterinaria

editarLa actividad biológica de las cucurbitacinas ha sido reconocida por centurias como un laxante y emético (vomitivo) y en el tratamiento de la malaria, la disentería y la dismenorrea.[cita 2] El zapallito silvestre argentino, Cucurbita andreana, se utilizó como purgante en medicina y veterinaria pero debido a sus efectos tóxicos, su uso fue suprimido en 1943 por el Codex medicamentarius argentino y en 1968 no se recetaba ya para los caballos (Millán 1968[16]).

Más recientemente, las cucurbitacinas han recibido mucha atención debido a sus propiedades antitumorales, y su toxicidad diferencial hacia las líneas celulares de tumores renales, cerebrales, y melanomas; su inhibición de la adhesión celular, y sus posibles efectos antifúngicos.[cita 2][24][25][26][27][28]

Como atractores de insectos

editarSi bien las cucurbitacinas son mortales o repelentes para la mayoría de los herbívoros vertebrados o invertebrados[cita 3], incluidos insectos[cita 4], algunas especies de escarabajos crisomélidos Aulacophorina y Diabroticina se alimentan de ellas como larvas o adultos[cita 5][cita 6], y las secuestran en sus tejidos y en la prole para su propia defensa.[cita 1][cita 7][cita 8] Los adultos pueden localizar las cucurbitacinas volatilizadas de las fragancias florales o de frutos heridos desde largas distancias.[cita 9][cita 10][cita 11] El 99% de los insectos atraídos a los frutos partidos y a las trampas son machos.[cita 12] Los que no se alimentan de cucurbitáceas como larvas sino que las buscan como adultos para secuestro de cucurbitacinas han sido descriptos como "farmacófagos" por Nishida y Fukami (1990[36]) porque las buscan por un fin diferente del metabolismo primario o reconocimiento del huésped.[cita 13] Obtenidas durante su alimentación como larvas o por farmacofagia, las cucurbitacinas persisten en la cutícula, los cuerpos grasos y la hemolinfa, y proveen protección ante los predadores.[cita 14] Quizás debido a sus beneficios para la defensa, las cucurbitacinas (como los alcaloides pirrolizidinos pyrrolizidine alkaloids) también se han vuelto un componente integral del comportamiento reproductivo de las especies que lo secuestran. En ambos casos, el agente farmacofágico es consumido directamente por las hembras o es secuestrado por los machos y pasado a las hembras a través de los espermatóforos, quienes a su vez, envían la mayor parte de este material a los huevos en desarrollo.[cita 14]

Se han hecho trampas para estos insectos utilizando esencia floral de Cucurbita maxima simplificada como atractor, que probaron disminuir el tamaño poblacional de estas especies y todavía se utilizan, si bien el 99% de los insectos atraídos son machos.[cita 15][cita 16]

Variantes

editarLas cucurbitacinas incluyen, al 2005:

Cucurbitacina A

editar- Cucurbitacina A, en algunas especies de Cucumis[15]: 1

- Pentanorcucurbitacina A, o 22-hydroxy-23,24,25,26,27-pentanorcucurbita-5-en-3-ona C

25H

40O

2, un polvo blanco[59]: 1

- Pentanorcucurbitacina A, o 22-hydroxy-23,24,25,26,27-pentanorcucurbita-5-en-3-ona C

Cucurbitacina B

editar- Cucurbitacina B proveniente de Hemsleya endecaphylla (62 mg/72 g)[60]: 4 y otras plantas; anti inflamatoirio y anti hepatotóxico[15]: 2

- Cucurbitacina B 2-O-glucoside, de Begonia heracleifolia[15]: 3

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina B de Hemsleya endecaphylla, 49 mg/72 g[59]: 5

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina B 2-O-glucósido de la raíz Picrorhiza kurrooa[15]: 4

- Deacetoxicucurbitacina B 2-O-glucósido de la raíz Picrorhiza kurrooa[15]: 5

- Isocucurbitacina B, de Echinocystis fabacea[15]: 6

- 23,24-Dihidroisocucurbitacina B 3-glucósido de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 7

- 23,24-Dihidro-3-epi-isocucurbitacina B, de Bryonia verrucosa[15]: 8

- Pentanorcucurbitacina B o ácido 3,7-dioxo-23,24,25,26,27-pentanorcucurbita-5-en-22-oico, C

25H

36O

4, polvo blanco[60]: 2

Cucurbitacina C

editar- Cucurbitacina C, de Cucumis sativus[15]: 11

Cucurbitacina D

editar- Cucurbitacina D, de Trichosanthes kirilowii y otras plantas.[15]: 12

- 3-Epi-isocucurbitacina D, de varias especies de Physocarpus[15]: 14 y Phormium tenax[61]

- 22-Deoxocucurbitacina D de Hemsleya endecaphylla, 14 mg/72 g[59]: 6

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina D de Trichosanthes kirilowii[15]: 13 y también de H. endecaphylla, 80 mg/72 g[59]: 3

- 23,24-Dihidro-epi-isocucurbitacina D, de Acanthosicyos horridus[15]: 20

- 22-Deoxocucurbitacina D de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 21

- Anhidro-22-deoxo-3-epi-isocucurbitacina D de Ecballium elaterium[15]: 22

- 25-O-Acetil-2-deoxicucurbitacina D (amarinina) de Luffa amara[15]: 24

- 2-Deoxicucurbitacina D, de Sloanea zuliaensis[15]: 23

Cucurbitacina E

editar- Cucurbitacina E (elaterina), de la raíz Wilbrandia ebracteata.[15]: 27

- 22,23-Dihidrocucurbitacina E de Hemsleya endecaphylla, 9 mg/72 g[59]: 8 , y raíz de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 28

- 22,23-Dihidrocucurbitacina E 2-glucósido de la raíz de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 29

- Isocucurbitacina E, de Cucumis phrophetarum[15]: 30

- 23,24-Dihidroisocucurbitacina E, de Cucumis phrophetarum[15]: 31

Cucurbitacina F

editar- Cucurbitacina F de Elaeocarpus dolichostylus[15]: 33

- Cucurbitacina F 25-acetato de Helmseya graciliflora[15]: 34

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina F de Helmseya amabilis[15]: 35

- 25-Acetoxi-23,24-dihidrocucurbitacina F de Helmseya amabilis (hemslecin A)[15]: 36

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina F glucósido de Helmseya amabilis[15]: 40

- Cucurbitacina II glucósido de Helmseya amabilis[15]: 41

- Hexanorcucurbitacina F de Elaeocarpus dolichostylus[15]: 43

- Perseapicrosida A de Persea mexicana[15]: 44

- Escandenosida R9 de Hemsleya panacis-scandens[15]: 45

- 15-Oxo-cucurbitacina F de Cowania mexicana[15]: 46

- 15-oxo-23,24-dihidrocucurbitacina F de Cowania mexicana[15]: 47

- Datiscósidos B, D, y H, de Datisca glomerata[15]: 48–50

Cucurbitacina G

editar- Cucurbitacina G de la raíz de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 52

- 3-Epi-isocucurbitacina G, de la raíz de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 54

Cucurbitacina H

editar- Cucurbitacina H, estereoisómero o cucurbitacina G, de la raíz de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 53

Cucurbitacina I

editar- Cucurbitacina I (elatericina B) de Hemsleya endecaphylla, 10 mg/72 g[59]: 7 ,de Ecballium elaterium y Citrullus colocynthis, disuade de alimentarse a los escarabajos pulga[15]: 55

- Hexanorcucurbitacina I de Ecballium elaterium[15]: 56

- 23,24-Dihidrocucurbitacina I ver Cucurbitacina L

- Khekadaengósidos D y K de la fruta de Trichosanthes tricuspidata[15]: 57, 58

- 11-Deoxocucurbitacina I, de Desfontainia spinosa[15]: 59

- Espinósidos A y B, de Desfontainia spinosa[15]: 61, 62

- 23,24-dihidro-11-Deoxocucurbitacina I de Desfontainia spinosa[15]: 60

Cucurbitacina J

editar- Cucurbitacina J from Iberis amara[15]: 69

- Cucurbitacina J 2-O-β-glucopyranoside de Trichosanthes tricuspidata[15]: 71

Cucurbitacina K

editar- Cucurbitacina K, un estereoisómero de la cucurbitacina J,[62]: 2 , de Iberis amara[15]: 70

- Cucurbitacina K 2-O-β-glucopiranósido de Trichosanthes tricuspidata[15]: 72

Cucurbitacina L

editar- Cucurbitacina L, o 23,24-dihidrocucurbitacina I,[15]: 63 [62]: 1

- Bridiósido A de Bryonia dioica[15]: 64

- Brioamárido de Bryonia dioica[15]: 65

- 25-O-Acetilbryoamárido de Trichosanthes tricuspidata[15]: 66

- Kekadengósidos A y B de Trichosanthes tricuspidata[15]: 67–68

Cucurbitacina O

editar- Cucurbitacina O de Brandegea bigelovii[15]: 73

- Cucurbitacina Q 2-O-glucósido, de Picrorhiza kurrooa[15]: 76

- 16-Deoxi-D-16-hexanorcucurbitacina O de Ecballium elaterium[15]: 77

- Deacetilpicracina de Picrorhiza scrophulariaeflora[15]: 78

- Deacetilpicracina 2-O-glucósido de Picrorhiza scrophulariaeflora[15]: 80

- 22-Deoxocucurbitacina O de Wilbrandia ebracteata[15]: 83

Cucurbitacina P

editar- Cucurbitacina P de Brandegea bigelovii[15]: 74

- Picracina de Picrorhiza scrophulariaeflora[15]: 79

- Picracina 2-O-glucósido de Picrorhiza scrophulariaeflora[15]: 79

Cucurbitacina Q

editar- Cucurbitacina Q de Brandegea bigelovii[15]: 75

- 23,24-Dihidrodeacetilpicracina 2-O-glucósido de Picrorhiza kurrooa[15]: 82

- Cucurbitacina Q1 de varias especies de Cucumis, se trata en realidad del compuesto Cucurbitacina F 25-acetato[15]

Cucurbitacina R

editar- Cucurbitacina R que es de hecho 23,24-dihidrocucurbitacina D.[15]

Cucurbitacina S

editar- Cucurbitacina S de Bryonia dioica[15]: 84, 85

Cucurbitacina T

editar- Cucurbitacina T, de la fruta de Citrullus colocynthis[15]: 86

28/29 Norcucurbitacinas

editarExisten varias sustancias que pueden considerarse derivadas del esqueleto cucurbita-5-eno por pérdida de uno de los grupos metilo (el 28 o 29) que se encuentran unidos al carbono 4; a menudo se observa que también el anillo adyacente (el anillo A) se convierte en aromático.[15]: 87–130

Colocintina

editarNota: averiguar si en nomenclatura moderna es alguna de las anteriores.

"La sustancia amarga (de Cucurbita andreana) es, entre otras, la colocintina (Paulsen 1936[63]). La colocintina se extrae de Citrullus colocynthis, donde primeramente fue descubierta, pero también la contienen otras cucurbitáceas." (Millán 1945[64])

Notas

editar- ↑ Saltar a: a b Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.70-71) "Cucurbitacins are produced in at least some tissues of all members of the Cucurbitaceae (Gibbs 1974,[2] Guha and Sen 1975,[3] Jeffrey 1980[4]) and a few species in other plant families (Curtis and Meade 1971,[5] Pohlman 1975,[6] Dryer and Trousdale 1978,[7] Thorne 1981[8]). In most species they are concentrated in roots and fruits, with lesser amounts in stems and leaves. Because of their extreme bitterness, cucurbitacins are thought to be involved in plant protection against herbivores (Metcalf 1985,[9] Tallamy and Krischik 1989[10]). Nevertheless, cucurbitacins are phagostimulants for both adults (Metcalf et al. 1980[11]) and larvae (DeHeer and Tallamy 1991[12]) of several luperine species in the subtribes Aulacophorina and Diabroticina (Table 4.1) and can have important ecological consequences for plants that possess them (Tallamy and Krischik 1989[10]). Adult luperines can detect cucurbitacins in nanogram quantities and readily devour bitter plant material (Metcalf 1994,[13] Tallamy et al. 1998[14]). In addition to WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera], cucurbitacins influence the behaviour of several important crop pests, including Diabrotica balteata LeConte, the banded cucumber beetle, Diabrotica barberi Smith and Lawrence, the northern corn rootworm, Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber, the southern corn rootworm, and Diabrotica speciosa, a crop pest in Central and South America." Tabla 4.1 lista los insectos fagostimulados por cada cucurbitacina (incluye datos no publicados).

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.70) "The biological activity of [cucurbitacins] has been recognized for centuries as a laxative and emetic and in the treatment of malaria, dysentery and dysmenorrhoea (Lavie and Glotter 1971,[17] Halaweish 1987,[18] Miro 1995[19]). More recently, cucurbitacins have received a great deal of attention because of their antitumour properties, differential cytotoxicity towards renal, brain tumour and melanoma cell lines (Cardellina et al. 1990,[20] Fuller et al. 1994[21]); their inhibition of cell adhesion (Musza et al. 1994[22]) and possible antifungal effects (Bar-Nun and Mayer 1989[23])."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.72) "[Cucurbitacins have] extreme bitternes and... ability to kill or repel most invertebrate and vertebrate herbivores (David and Vallance 1955,[29] Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk 1962,[30] Nielsen et al. 1977,[31] Tallamy et al. 1997a[32])."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.67) "[Cucurbitacins have] Noxious effects on other [other than Diabrocitina and Aulacophorina] insects" (Nielsen et al. 1977,[31] Tallamy et al. 1997a[32]).

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.72) "Of greatest interest are the species of luperines that do not (and apparently cannot) feed on cucurbit roots as larvae, but consume pure crystalline cucurbitacins as adults when given the chance".

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.82) "As noted above, despite specialization on the Poaceae, adult WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera] and D. barberi feed compulsively on bitter cucurbitacins when presented the opportunity, and they are attracted to volatiles from Cucurbita blossoms (Metcalf and Metcalf 1992[33] and references therein)."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.67) "For more than a century, researchers have noted the curious attraction of adult luperine chrysomelids in the subtribes Diabrocitina and Aulacophorina to cucurbit species rich in the bitter compounds collectivelly called cucurbitacins (Webster 1895,[34] Contardi 1939,[35] Metcalf et al. 1980[11])".

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.72) "As discussed above, cucurbitacins are phagostimulants for many luperine adults (Metcalf et al. 1980,[11] Nishida and Fukami 1990,[36] Tallamy et al. 1997b[37]) and larvae (DeHeer and Tallamy 1991[12])".

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.67) "[Diabrocitina and Aulacophorina] can locate cucurbits over long distances by tracking flower and wound volatiles, and... cucurbitacins are phagostimulants for Diabroticites that... cause them to eat anything containing these compounds (Sinha and Krishna 1970,[38] Metcalf et al. 1980[11])."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.71-72). "Studies have shown that, when WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera] eat crystalline cucurbitacins for 2 days, they excrete 85% of the material and permanently sequester the remainder in their fat bodies, cuticles, haemolymph, spermatophores and developing eggs (Ferguson and Metcalf 1985,[39] Andersen et al. 1988,[40] Tallamy et al. 2000[41]). There is good evidence that, regardless of the cucurbitacin configuration eaten, beetles transform it through glycosilation, hydrogenation, desaturation and acetylation into 23,24-dihydrocucurbitacin D (Andersen et al. 1988,[40] Nishida et al. 1992[42]). There are decided defensive benefits to cucurbitacin sequestration. Beetles that have eaten cucurbitacins become highly distasteful and are readily rejected by predators such as mantids, mice and finches (Ferguson and Metcalf 1985,[39] Nishida and Fukami 1990,[36] DW Tallamy, unpublished data). Sequestered cucurbitacins may also discourage parasitoids such as tachinid flies in the genus Celatoria, although this has never been tested. Moreover, when cucurbitacins have been sequestered in eggs and larvae, both of which are denizens of pathogen-rich damp soil, survival after exposure to the entomopathogen Metarhizium anisopliae is significantly improved (Tallamy et al. 1998[14]). This may explain why females shunt 79% of the cucurbitacins that are not excreted into their eggs or the mucus coating of the eggs (Tallamy et al. 2000[41])."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.81-82) "Electroantennogram (EAG) recording was used to identify extract compounds attractive to Diabrocites, citing: Hibbard et al. (1997b[43]), Cossé and Baker (1999[44])."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.72)"Despite the benefits to female WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera] from eating bitter cucurbit tissues, it is males rather than females who actively seek these compounds in nature. In a field trial quantifying the sex ratio of beetles that came to cucurbitacin-rich fruits of Cucurbita andreana, Tallamy et al. (2002[45]) found that 99% of the 224 WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera] found at the fruits over a 5-day period were males. This result concurs with the male-biased sex ratios frequently found in cucurbitacin traps (Shaw et al. 1984;[46] Fielding and Ruesink 1985[47]). Apparently females rely on males for their primary source of cucurbitacins (Tallamy et al. 2000[41]). Males sequester 89% of the cucurbitacins not excreted after ingestion in their spermatophores and pass them to females during copulation. Whether such behaviour imparts a mating advantage to WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera] males has not been investigated."

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.73) "Luperines such as WCR [western corn rootworm, Diabrotica virgifera virgifera], have been described as pharmacophagous insects (Nishida and Fukami 1990[36]) because they search for particular phytochemicals for purposes other than primary metabolism or host recognition (Boppré 1990[48])."

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.73) "Whether obtained through pharmacophagy or specialization on cucurbits, cucurbitacins persist in the cuticle, fat bodies and haemolymph (Ferguson et al. 1985,[49] Andersen et al. 1988[40]) and provide protection against predators (Ferguson and Metcalf 1985,[39] Nishida and Fukami 1990[36]) and/or pathogens (Tallamy et al. 1998[14]). Perhaps because of their defensive benefits, both cucurbitacins and pyrrolizidine alkaloids have also become an integral component of the reproductive behaviour of participating species (Dussourd et al. 1991,[50] LaMunyon and Eisner 1993,[51] Tallamy et al. 2000[41]). In both cases, the pharmacophagous agent is consumed directly by females and/or is sequestered by males and passed whithin spermatophores to females. Females, in turn, shunt the majority of these materials to developing eggs".

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.81) "Diabrotica spp., in general, have been associated with blossoms of varying Cucurbita spp. (Fronk and Slater 1956,[52] Howe and Rhodes 1976,[53] Bach 1977,[54] Fisher et al. 1984[55]). Andersen and Metcalf (1987[56])... (found they preferred C. maxima over the other species)" (p.81) "Andersen (1987[57]) identified 22 of the 31 major components of C. maxima floral aroma. Metcalf and Lampman (1991[58] and references therein) evaluated them for attraction to diabroticite beetles... Metcalf and Metcalf (1992[33] and references therein) (developed a 3-component blend as a highly simplified Cucurbita blossom volatile aroma). (p.83) "Metcalf and Metcalf (1992[33])... added a methoxy group to natural compounds (that) dramatically increased its effectiveness in attracting adult beetles.... It is these more attractive methoxy analogues of natural compounds which are generally used as lures today".

- ↑ Tallamy et al. (2005[1]): (p.83-84-85) it mentions some real lures and if they are commercially availables, the most effective a new trap developed by Trécé (Salinas, California) containing buffalo gourd root powder.

Referencias

editar- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n ñ o Tallamy DW, BE Hibbard, TL Clark and JJ Gillespie. 2005. Western Corn Rootworm, Cucurbits and Cucurbitacins. In: S Vidal et al. (eds.) 2005. Western Corn Rootworm: Ecology and Management CAB International. Chapter 4. «Copia archivada». Archivado desde el original el 29 de noviembre de 2014. Consultado el 23 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ Gibbs, R.D. (1974) Chemotaxonomy of Flowering Plants 2. McGill-Queen’s University Press. Montreal and London, pp. 829–830, 843, 1255–1259

- ↑ Guha, J. and Sen, S.P. (1975) The cucurbitacins – a review. Journal of Plant Biochemistry 2, 12–28

- ↑ Jeffrey, C. (1980) A review of the Cucurbitaceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 81, 233–247.

- ↑ Curtis, P.S. and Meade, P.M. (1971) Cucurbitacins from Crusiferae. Phytochemistry 10, 3081–3083

- ↑ Pohlman, J. (1975) Die Cucurbitacine in Bryonia alba und Bryonia dioica. Phytochemistry 14, 1587–1589

- ↑ Dryer, D.L. y Trousdale, E.K. (1978) Cucurbitacins in Purshia tridentate. Phytochemistry 17, 325–326

- ↑ Thorne, R.F. (1981) Phytochemistry and angiosperm phylogeny, a summary statement. En: Young, D.A. and Seigler, D.F. (eds) Phytochemistry and Angiosperm Phylogeny. Praeger, New York, pp. 233–295.

- ↑ Metcalf, R.L. (1985) Plant kairomones and insect pest control. Bulletin III Natural History Survey 35, 175

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Tallamy, D.W. y Krischik, V.A. (1989) Variation and function of cucurbitacins in Cucurbita: an examination of current hypotheses. American Naturalist 133, 766–786

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d Metcalf RL, Metcalf RA y Rhodes AM (1980) Cucurbitacins as kairomones for diabroticite beetles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 17:3769-3772.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b DeHeer, C.J. y Tallamy, D.W. (1991) Cucumber beetle larval affinity to cucurbitacins. Environmental Entomology 20, 775–788

- ↑ Metcalf, R.L. (1994) Chemical ecology of Diabroticites. En: Jolivet, P.H. , Cox, M.L. y Petitpierre, E. (eds) Novel Aspects of the Biology of the Chrysomelidae. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, Massachusetts, pp. 153–169

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c Tallamy, D.W., Whittington, D.P., Defurio, F., Fontaine, D.A., Gorski, P.M. y Gothro, P. (1998) The effect of sequestered cucurbitacins on the pathogenicity of Metarhizium anisopliae (Moniliales: Moniliaceae) on spotted cucumber beetle eggs and larvae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Environmental Entomology 27, 366–372

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n ñ o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an añ ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bñ Jian Chao Chen, Ming Hua Chiu, Rui Lin Nie, Geoffrey A. Cordell and Samuel X. Qiu (2005), "Cucurbitacinas and cucurbitane glycosides: structures and biological activities" Natural Product Reports, volume 22, pages 386-399 doi 10.1039/B418841C

- ↑ Millán R (1968) Observaciones sobre cinco Cucurbitáceas cultivadas o indígenas en la Argentina. Darwiniana 14(4):654–660 http://www.jstor.org/stable/23213812

- ↑ Lavie, D. and Glotter, E. (1971) The cucurbitacins, a group of tetracyclic triterpenes. Fortschritte der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe 29, 306–362.

- ↑ Halaweish, F.T. (1987) Cucurbitacins in tissue cultures of Brionia dioica Jacq. PhD thesis, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK

- ↑ Miro, M. (1995) Cucurbitacins and their pharmacological effects. Phytotherapy Research 9, 159–168

- ↑ Cardellina, J.H., Gustafson, K.R., Beutler, J.A., McKee, C., Hallock, Y.F., Fuller, R.W. y Boyd, M.R. (1990) Human medicinal agents from plants. En: Kinghorn, A.D. y Balandrin, M.F. (eds) National Cancer Institute Intramural Research on Human Immunodeficiency Virus Inhibitory and Antitumor Plant Natural Products. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp. 218–227

- ↑ Fuller, R.W., Cardellina, J.H., II, Cragg, G.M. y Body, M.R. (1994) Cucurbitacin: differential cytotoxicity, dereplication and first isolation from Gonystylus keithii. Journal of Natural Products 57, 1442–1445

- ↑ Musza, L.L., Speight, P., McElhiney, S., Brown, C.T., Gillum, A.M,. Cooper, R. y Killar, L.M. (1994) Cucurbitacins: cell adhesion inhibitors from Conobea scoparioides. Journal of National Products 57, 1498–1502

- ↑ Bar-Nun, N. and Mayer, A.M. (1989) Cucurbitacins – repressor of induction of laccase formation. Phytochemistry 28, 1369–1371.

- ↑ Alghasham, AA (2013). «Cucurbitacinas - a promising target for cancer therapy». International journal of health sciences 7 (1): 77-89. PMC 3612419. PMID 23559908.

- ↑ Kapoor, S (2013). «Cucurbitacina B and Its Rapidly Emerging Role in the Management of Systemic Malignancies Besides Lung Carcinomas». Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals 28 (4): 359. PMID 23350897. doi:10.1089/cbr.2012.1373.

- ↑ Ishii, T; Kira, N; Yoshida, T; Narahara, H (2013). «Cucurbitacina D induces growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in human endometrial and ovarian cancer cells». Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine 34 (1): 285-91. PMID 23150173. doi:10.1007/s13277-012-0549-2.

- ↑ Lui, VW; Yau, DM; Wong, EY; Ng, YK; Lau, CP; Ho, Y; Chan, JP; Hong, B; Ho, K; Cheung, CS; Tsang, CM; Tsao, SW; Chan, AT (2009). «Cucurbitacina I elicits anoikis sensitization, inhibits cellular invasion and in vivo tumor formation ability of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells». Carcinogenesis 30 (12): 2085-94. PMID 19843642. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgp253.

- ↑ Sun, J; Blaskovich, MA; Jove, R; Livingston, SK; Coppola, D; Sebti, SM (2005). «Cucurbitacina Q: A selective STAT3 activation inhibitor with potent antitumor activity». Oncogene 24 (20): 3236-45. PMID 15735720. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208470.

- ↑ David, A. y Vallance, D.K. (1955) Bitter principles of Cucurbitaceae. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 7, 295–296.

- ↑ Watt, J.M. y Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. (1962) The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa 2nd edn. E. & S. Livingstone, Edinburgh.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Nielsen JK, Larsen M and Sorenson HJ (1977) Cucurbitacins E and I in Iberis amara feeding inhibitors for Phyllotreta nemorum. Phytochemistry 16:1519-1522.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Tallamy DW, Stull J, Erhesman N and Mason CE. 1997. Cucurbitacins as feeding and oviposition deterrents in nonadapted insects. Environmental Entomology 26:678-688.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c Metcalf, R.L. y Metcalf, E.R. (1992) Plant Kairomones in Insect Ecology and Control. Routledge, Chapman and Hall, New York

- ↑ Webster FM (1895) On the probable origin, development and diffusion of North American species of the genus Diabrotica. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 3:158-166.

- ↑ Contardi, GH. 1939. Estudios genéticos en Cucurbita y consideraciones agronómicas. Physis 18:331-347.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d e Nishida R and Fukami H (1990) Sequestration of distasteful compounds by some pharmacophagous insects. Journal of Insect Physiology 40:913-931.

- ↑ Tallamy, D.W., Gorski, P.M. and Pesek, J. (1997b) Intra- and interspecific genetic variation in the gustatory perception of cucurbitacins by diabroticite rootworms (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Environmental Entomology 26, 1364–1372.

- ↑ Sinha AK, y Krishna SS (1970). Further studies on the feeding behavior Aulacophora foveicollis on cucurbitacin. Journal of Economic Entomology 63:333-334.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c Ferguson, J.E. y Metcalf, R.L. (1985) Cucurbitacins: plant derived defense compounds for Diabroticina (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Journal of Chemical Ecology 11, 311–318.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c Andersen JF, RD Plattner y D Weisleder. 1988. Metabolic transformations of cucurbitacins by Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte and D. undecimpunctata howardi Barber. Insect Biochemistry 19:71-78.

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d Tallamy, D.W., Gorski, P.M. y Burzon, J.K. (2000) The fate of male-dervied cucurbitacins in spotted cucumber beetle females. Journal of Chemical Ecology 26, 413–427

- ↑ Nishida, R., Yokoyama, M. y Fukami, H. (1992) Sequestration of cucurbitacin analogs by New and Old World chrysomelids leaf beetles in the tribe Luperini. Chemoecology 3, 19–24

- ↑ Hibbard, B.E., Randolph, T.L., Bernklau, E.J. y Bjostad, L.B. (1997b) Electro-antennogram-active components of buffalo gourd root powder for western corn rootworm adults (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Environmental Entomology 26, 1136–1142.

- ↑ Cossé, A.A. y Baker, T.C. (1999) Electrophysiologically and behaviorally active volatiles of buffalo gourd root powder for corn rootworm beetles. Journal of Chemical Ecology 25, 51–66.

- ↑ Tallamy, D.W., Powell, B.E. y McClafferty, J.A. (2002) Male traits under cryptic female choice in the spotted cucumber beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Behavioral Ecology 13, 511–518

- ↑ Shaw, J.T., Ruesink, W.G., Briggs, S.P. y Luckman, W.H. (1984) Monitoring populations of corn rootworm beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) with a trap baited with cucurbitacins. Journal of Economic Entomology 77, 1495–1499

- ↑ Fielding, D.J. y Ruesink, W.G. (1985) Varying amounts of bait influences numbers of western and northern corn rootworms (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) caught in cucurbitacins traps. Journal of Econonomic Entomology 78, 1138–1144

- ↑ Boppré, M. (1990) Lepidoptera and pyrrolizidine alkaloids: exemplification of complexity in chemical ecology. Journal of Chemical Ecology 16, 165–180

- ↑ No hay tal "Ferguson et al. 1985" Puede haberse referido a "Ferguson et al. 1983": Ferguson, J.E., Metcalf, E.R., Metcalf, R.L. y Rhodes, A.M. (1983) Influence of cucurbitacin content in cotyledons of Cucurbitaceae cultivars upon feeding behavior of Diabroticina beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 76, 47–57

- ↑ Dussourd, D.E., Harvis, C.A., Meinwald, J. and Eisner, T. (1991) Pheromonal advertisement of a nuptial gift by a male moth (Utethesia ornatrix). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 88, 9224–9227.

- ↑ LaMunyon, C.W. and Eisner, T. (1993) Postcopulatory sexual selection in an arctiid moth (Utethesia ornatrix). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 90, 4689–4692

- ↑ Fronk, W.D. y Slater, J.H. (1956) Insect fauna of cucurbit flowers. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 29, 141–145

- ↑ Howe, W.L. y Rhodes, A.M. (1976) Phytophagous insect association with Cucurbita in Illinois. Environmental Entomology 5, 747–751

- ↑ Bach, C.E. (1977) Distribution of Acalymma vittata and Diabrotica virgifera (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on Cucurbita. Great Lakes Entomologist 10, 123–125.

- ↑ Fisher, J.R., Branson, T.F. y Sutter, G.R. (1984) Use of common squash cultivars, Cucurbita spp., for mass collection of corn rootworm beetles, Diabrotica spp. (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society J 57, 409–412

- ↑ Andersen JF y RL Metcalf. 1987. Factors influencing distribution of Diabrotica spp. in blossoms of cultivated Cucurbita spp. Journal of Chemical Ecology 13:681-699.

- ↑ Andersen JF. 1987. Composition of the floral odor of Cucurbita maxima Duchesne (Cucurbitaceae). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 35:60-62.

- ↑ Metcalf, R.L. y Lampman, R.L. (1991) Evolution of diabroticite rootworm beetle (Chrysomelidae) receptors for Cucurbita blossom volatiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 88, 1869–1872

- ↑ Saltar a: a b c d e f Jian-Chao Chen, Gao-Hong Zhang, Zhong-Quan Zhang, Ming-Hua Qiu, Yong-Tang Zheng, Liu-Meng Yang, Kai-Bei Yu (2008), "Octanorcucurbitane and Cucurbitane Triterpenoids from the Tubers of Hemsleya endecaphylla with HIV-1 Inhibitory Activity". J. Nat. Prod. volume 71, pages 153–155 doi 10.1021/np0704396

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Chiy-Rong Chen, Yun-Wen Liao, Lai Wang, Yueh-Hsiung Kuo, Hung-Jen Liu, Wen-Ling Shih, Hsueh-Ling Cheng and Chi-I Chang (2010). "Cucurbitane Triterpenoids from Momordica charantia and Their Cytoprotective Activity in tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide-Induced Hepatotoxicity of HepG2 Cells". Chemical & pharmaceutical bulletin, volume 58, issue 12, pages 1639-1642. doi 10.1248/cpb.58.1639

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031942200942237

- ↑ Saltar a: a b Da-Cheng Wang, Hong-Yu Pan, Xu-Ming Deng, Hua Xiang, Hui-Yuan Gao, Hui Cai, and Li-Jun Wu (2007), "Cucurbitane and hexanorcucurbitane glycosides from the fruits of Cucurbita pepo cv dayangua". Journal of Asian Natural Products Research, volume 9, issue 6, pages 525–529.

- ↑ Paulsen, EF. 1936. Sobre el aislamiento de los principios amargo del fruto de Cucurbita andreana. Rev. Arg. Agr. 3(4): 250-252.

- ↑ Millán R, 1945. Variaciones del zapallito amargo Cucurbita andreana y el origen de Cucurbita maxima. Revista Argentina de Agronomía 12:86-93.

Enlaces externos

editar- Esta obra contiene una traducción derivada de «Cucurbitacinaa» de Wikipedia en inglés, publicada por sus editores bajo la Licencia de documentación libre de GNU y la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.